VoC Dispatch: April 2022

André Bazin, the Catholic Imagination Conference, and National Canadian Film Day

In this newsletter: André Bazin, the Catholic Imagination Conference, National Canadian Film Day, and some links.

André Bazin: A Chronological Bibliography

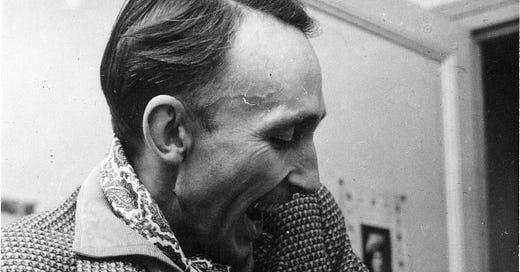

April 18 marks the birthday of the great film critic and theorist André Bazin, who died in 1958 at the age of 40. Controversial and beloved in his own time, Bazin was easily the most important intellectual figure of the post-war French film scene, and, depending on who you ask, the most important film theorist who ever lived.

He was also a complex character who reflected the France of his time. In his genesis as a thinker, we can see the dualistic influences of the education system that formed him: an ethos caught between 19th century rationalist and positivist principles and the 20th century’s awakening to the mysterious via Henri Bergson, Catholic revivalism, and surrealism. In his mature period, we can see the influence of contemporary developments in existentialism, phenomenology, art history, and psychology. Encompassing all of these is the murky question of Bazin’s Catholicism, which seems to have been tied less to personal faith than to its role in social activism of the 1930s and 40s - most of all to Emmanuel Mounier’s philosophy of Personalism - and yet which clearly gifted to him a profoundly theological imagination.

Bazin was a stunningly prolific writer, penning over 2600 pieces in fifteen years of unceasing activity. Of that number, somewhere between 150 and 200 have been published in English. Many of those essays are by Bazin’s own reckoning his most important works, as a good number of them were lifted from Qu’est ce que le cinéma ?, a four volume collection of his work which he was in the process of editing and publishing when he died - but their initial arrival in English was unfortunately marred by unnecessary confusion.

Bazin never wrote his essays with the intention of crafting a systematic theory of cinema, but given the opportunity to collect his work, he decided to organize his most significant writings into a somewhat systemized treatment of the fundamental question: “What is cinema?” Beginning with Volume One’s focus on ontology and language, the question expands in Volume Two to cinema’s relationship among the arts, followed by Volume Three’s focus on sociology, and concludes with a case study of neorealism in Volume Four.

This structure was hollowed out and all but lost when What Is Cinema? was published in English via two mashed-up volumes in the late 1960s. While this did not stop Bazin from having a profound influence on Anglo-American film studies - indeed, the effect of those two mangled books was enormous - it did introduce a certain arbitrary sense for how to approach Bazin. Beyond the essential starting point of his 1945 essay The Ontology of the Photographic Image, a staple of first-year film history courses, it seemed like Bazin could be sampled more or less in whatever order one felt was best.

As anyone who reads Bazin finds out quickly, the profundity of his thought does not exactly lend itself to a sporadic or ‘greatest hits’ approach. The human mind longs to see the bigger picture and in lieu of an actual systemized treatment, it naturally falls to the historical development of a person’s thought to fill in the gaps. At least, this is what I found last year when I fell into a chronological reading of Bazin’s thought via a collection of early essays, French Cinema of the Occupation and Resistance, which arranges its selections in order of publication from 1943 to 1946.

The experience was revelatory. Seeing the young Bazin’s ideas and language develop from piece to piece was compelling, and made it much easier to grasp his train of thought than the ways in which he is usually taught. Bazin as a writer and thinker came alive for me in a way he hadn’t before. Suddenly I could accompany him as he tried things out, circled back to ideas, and deepened his concepts. It became possible to get to know him, and by extension, understand not only the ideas themselves, but begin to intuit why they fascinated him.

Inspired by this experience, I assembled a chronological bibliography of Bazin’s available works in English, cross-referencing titles and dates with Yale’s indispensable database of Bazin’s complete writings.1 The list is not complete - who knows if it ever will be truly complete - but I hope it will still be helpful to those who wish to grasp Bazin’s thought as it evolved and grew.

And while the list will be of most benefit to those who have access to many or all of these writings, I think the method can still be fruitfully applied even to the reading of What is Cinema?, which for all of its flaws remains the most significant single Bazin collection in English. Just give it a try, and see what you find.

I look forward to sharing more about this great thinker soon. More than 60 years after his passing, Bazin still has much to say to us. Indeed, he is only getting started.

Catholic Imagination Conference

Registration has opened for the 2022 edition of the Catholic Imagination Conference, hosted this fall at the University of Dallas. I’m excited to share that I will be attending. Here is the description for this year’s focus:

What is the future of the Catholic literary and artistic tradition? What is the state of faith-laced discourse in a world increasingly characterized by schism and brokenness? How is Catholic thought and practice particularly well suited to address universal human needs such as redemption, forgiveness, community, and hope?

As someone who began paying close attention to the Catholic literary conversation only relatively recently, it has been fascinating to see how much ground has been covered in the last ten years. In his seminal 2013 essay, The Catholic Writer Today, the poet Dana Gioia pondered the mystery of a modern Catholic literary tradition in decline. As Gioia and others in his wake noted, the unapologetically Catholic writer as a mainstay of contemporary literary culture seemed to have quietly dropped off the map. This was a deeply puzzling development because for almost as long as the modern novel has existed as a form, there have been major Catholic and other Christian writers at the forefront of mainstream literature: in England, it was a line that ran for a hundred years from St. John Henry Newman to Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene; in France, from J.K. Huysmans and Leon Bloy to the final works of Francois Mauriac; and of course in the U.S. and Canada there was the mid-century dominance of Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, J.F. Powers, and Morley Callaghan, among many others - and that’s not even getting into the subject of poetry.

Long story short, Gioia’s essay touched off a brushfire of discussion which has happily bloomed into a much bigger blaze. In the North American context alone, a host of new Catholic publishing labels have been both founded and have found their footing, new fiction by Catholic writers is being published at a genuinely astonishing rate, and the theoretical discussion which Gioia ignited has deepened into a rich discourse probing historical, philosophical, and theological questions of great significance. Perhaps most exciting of all has been a slow but undeniable rediscovery and republishing of thinkers like Jacques Maritain, Étienne Gilson, and Dietrich von Hildebrand, all of whom wrote extensively on modern aesthetics, and who have much to offer us in our particular predicaments today as writers, poets and… filmmakers?

Yes, filmmakers. This brings me back to why I’m attending the CIC. The unique role of moving images in the ‘Catholic Imagination’ remains severely underdeveloped, and short of a major intellectual and artistic renewal, it will remain so for the foreseeable future. One of my hopes in attending the CIC is to meet others interested in sparking that intellectual renewal by exploring the philosophy of cinema, its relationship to reality, and its deep kinship with both literary realism and modern poetry.

Even further, just as it is possible for a novelist or a poet to ply their trade from wherever they live, perhaps the time has come for Catholics to take a leading role in reimagining the identity of cinema as the kin of poetry; as something which, practically-speaking, can and ought to be done wherever filmmakers have been planted by Divine Providence. Perhaps it will be possible to imagine and begin building a cinema which is free from the crushing constraints and demands of a massive industry.

What I am not interested in discussing is: how Christians can infiltrate Hollywood, the importance of three-act structure, or how making Biblical or saint films is the natural calling of a Catholic filmmaker. These are unfortunately American-centric conversations which have long run their course and are too tied to the limited and finite ethos of Hollywood production models. It’s time for a new conversation entirely about the nature of cinema and its role in the theological destiny of man. It’s time to get down to the roots of cinema itself. I don’t believe that there will be a legitimately fruitful flourishing or renewal of cinematic culture within Catholicism without this foundational step.

If these sound like conversations you’re interested in having, let’s hang out in Dallas this fall! Or, failing that, let’s start the conversation now - just reply to this email.

See you in September!

National Canadian Film Day

April 20 marks National Canadian Film Day, which is not a real holiday but nonetheless gives Canadian filmmakers an opportunity to remind a nation of 38 million mostly-Hollywood custumers that some of their fellow citizens also make films.

Since I’m a Canadian filmmaker, I hope you don’t mind if I jump on this opportunity to introduce VoC readers to my own work. Since 2015, I’ve made three fiction shorts which explore the potentiality of cinema as a medium of narrative realism. Here’s a brief rundown:

Son in the Barbershop (2015)

A teenager overhears a phone call and inserts himself into the father-son story behind it. (7 min)

Son in the Barbershop is a stab at the kind of immersive and naturalistic realism that remains the bread and butter of certain echelons of the film festival circuit. It’s a 7-minute, one-shot film which attempts to tell a short story under the formal constraints of a single take.

Cave of Sighs (2016)

A casual hook-up becomes waylaid by unusual circumstances - a collection of Byzantine icons. Note: Mature viewers only. (10 min)

Cave of Sighs goes in the opposite direction from the previous film by shooting and editing in a more conventional manner, but with an eye towards creating a kind of psychological space which is open to the possibility of a mystical encounter.

La Cartographe (2018)

A young woman investigates her neighbour and his wildly boring running route. (34 min)

La Cartographe is in some ways a synthesis of the concerns of the other films - naturalism and mysticism - into one film. In the years since making it, I’ve come to see more clearly that its interests are sacramental in nature; for it is concerned with characters who begin to discern how certain places, people, and behaviours are pregnant with - and signify - deeper realities.

Whether you watch one film, half of a film, or all three, I appreciate you taking the time to do so. If you have thoughts to share, my inbox is always open - just hit reply to this email. :)

Links

Things I’ve been enjoying of late…

Will Tavlin dives into the devastating details of Hollywood’s still-ongoing Quiet Revolution: the conversion from celluloid to digital distribution. (n+1 Magazine)

In a touching essay, Casie Dodd reflects on Walker Percy’s role in the interregnums of her spiritual journey. (Church Life Journal)

In a brisk and detailed account, Matthew J. Franck considers the strange history of the Hollywood Biblical epic. (The Public Discourse)

Listen: Thomas Mirus interviews Dappled Things editor Katy Carl on her new novel, As Earth Without Water. What begins as as an interview becomes a genuine dialogue between two artists. (Catholic Culture Podcast)

Watch: Whether you’re interested in Marvel films or not, there is no question that they constitute the cutting edge of industrial filmmaking today. To learn about them is to learn something about mainstream film aesthetics as a whole. What do we find? That contemporary visual effects are more complex, skill-intensive, and unmoored from physical reality than ever before. This video does a terrifyingly great job at showing how much the modern ‘cinema of attractions’ has become more virtual than actual at nearly every level - and yet the virtues necessary to produce a well-done work of this kind remain impossible to dismiss. (Vanity Fair)

Postscripts

“To him, cinema was a vast ecological system, endlessly interesting in its interdependencies and fluctuations… No one before him, and maybe no one after, has so intuitively traveled with a film into the capillary networks that give it life.” - Dudley Andrew, André Bazin (p. xxiv)

“[Bazin’s] modernism belongs to a strain that adamantly avoids the simple division between elite and popular art that has increasingly marred recent critical discussion. It may be among Bazin’s most important claims to supremacy as a critic that in his work the mainstream and the avant-garde coexist so easily.” - Colin MacCabe, “Bazin As Modernist” in Opening Bazin: Postwar Film Theory & It’s Afterlife

As with so many Bazinian initiatives in English-language film studies, we owe a great debt to Dudley Andrew and his assistants, as well as to Hervé Joubert-Laurencin for spearheading the same project in France.